Policymakers in several African countries are on the wrong side of the medical professionals "brain drain" debate

The solution to high-skill emigration ought to be to expand and raise the standards of training medical professionals, not blanket bans on emigration

A number of African countries (see here, here, and here) have recently passed laws or promulgated policies designed to stem the emigration of scarce medical professionals. While the region’s acute shortage of healthcare professionals is a real concern, blanket emigration bans are likely to exacerbate the problem by shrinking the pipeline of future doctors and denying medical schools opportunities for improvement. In addition, countries that restrict emigration stand to miss out on remittances that, at least in the case of medical doctors, have been shown to more than pay for the typical cost of training.

I: African countries face a severe shortage of healthcare professionals

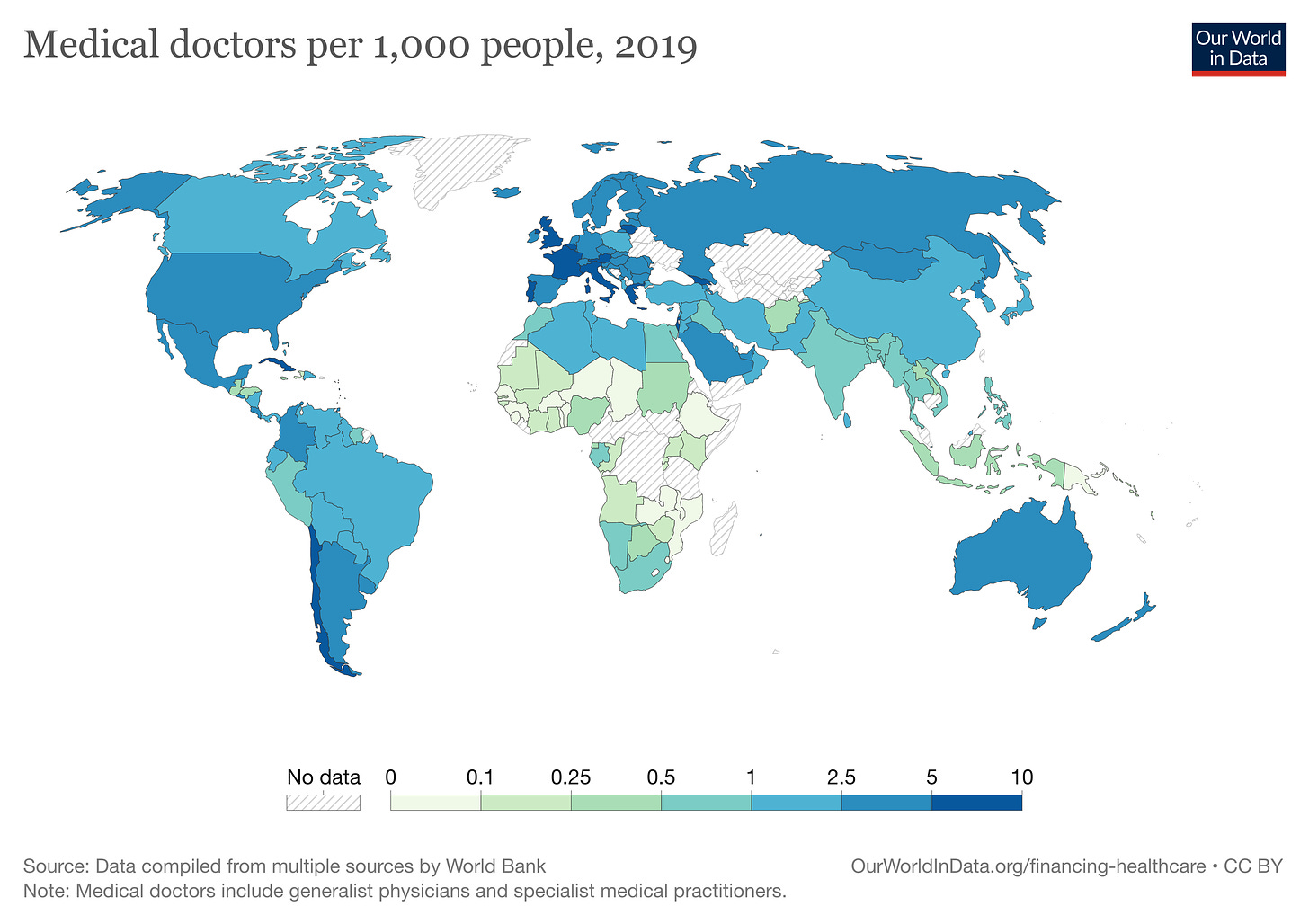

There is a significant shortage of doctors and other medication professionals in Africa. For example, according to the standard measure of physicians per 1000 people, the region (0.2) lags the world average (1.6). Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, stands at about a quarter the global average (0.4), while Kenya (0.2), Malawi (0.05) and others are even lower. Even relatively wealthier South Africa (0.8) is below the global average. The effects of the shortage are likely to worsen as rising incomes and higher life expectancy in the region create demand for treatment of “lifestyle diseases” and chronic medical conditions requiring specialized care.

Although there is no ideal average number of physicians per capita (accessibility and effective health systems matter more), the World Health Organization generally recommends at least a 1:1000 ratio.

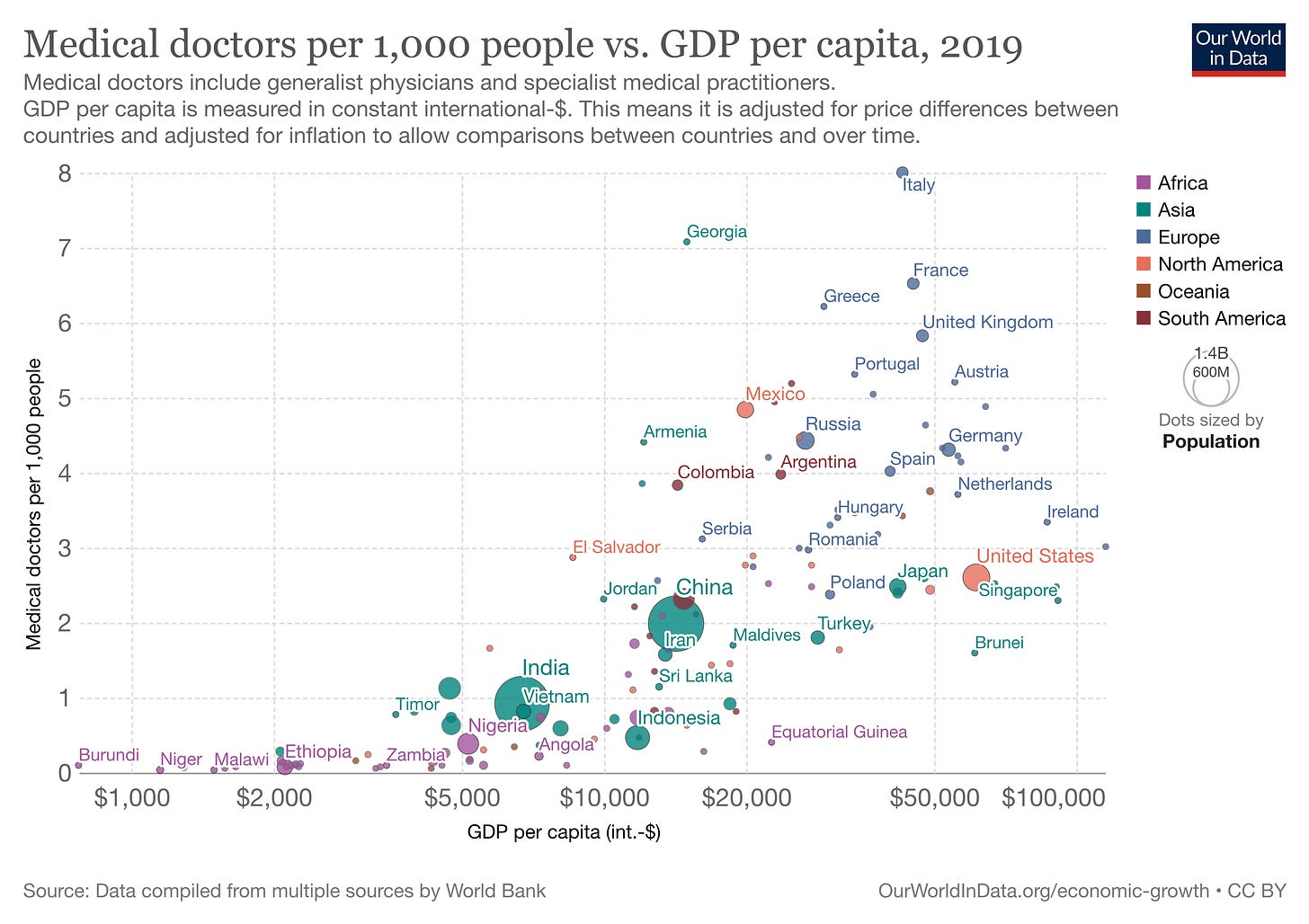

African countries are not unique in this regard. Around the world low-income countries struggle to maintain high doctor/patient ratios. The data suggests that countries below the $5,000 per capita mark also stay below the 1:1000 ratio. Worryingly for African countries, it looks like the region’s countries stay below the 1:1000 ration even after passing the $5,000 mark.

The national averages mask subnational variation (and the dire state of affairs). Given the higher concentrations of hospitals and medical professionals in urban areas, the shortage is much worse in rural areas (where a majority of Africans live) than the number suggest. For example, Nairobi County in Kenya (8% of the population) hosts 32% of doctors — a fact that enables it reach the 1:1000 WHO recommended ratio. Meanwhile, several peripheral counties have 0.01 doctors per 1000 residents.

The trend lines suggest that the supply of doctors over the last three decades can barely keep up with population growth in the region. Despite the economic turnaround that began in the mid-1990s, Africa as a region has not managed to accelerate the training of doctors ahead of population growth. As such, the ratio of doctors per 1000 resident has oscillated between 0.2 and 0.4. Interestingly, health outcomes have significantly improved in the region over the same time period. Infant mortality rates have declined from a high of 107 per 1000 live births in 1990 to 50 in 2021. Life expectancy at birth has increased from 50 to 61 years over the same period.

II: Policymakers are taking the wrong approach to address the shortage

Before thinking through potential policy responses, it is important to understand the reasons behind the undersupply of doctors in African states. A number of possible (complementary) explanations come to mind.

On the supply side, medical training may have been collateral damage in the decimation of African higher education in the 1970s (by insecure personalist autocrats) and the 1980s (by structural adjustment programs). Overall tertiary enrollment rates in African states stayed flat for decades and, despite recent upticks, continue to lag regions like East and South Asia (see figure below). Budget constraints also limited expansion of medical schools. In Kenya, between 1975-1990 the share of medical students at the university of Nairobi fell from 9% to 8.5%. In addition, the rise of Global Health as a field may have created strong disincentives against expansion of medical training since the improvements in health outcomes noted above could be achieved on the cheap with the help foreigners.

Historically weak demand likely compounded the supply side constraints indicated above. First, the region’s large share of relatively poor consumers of healthcare largely restricted demand for medical care to what fiscally-constrained governments could pay for. Therefore, focus was on infectious diseases that were responsible for the region’s high (infant) mortality rates. Government policy typically conceptualized the fight against these diseases as developmentalist public health.

Notice that treatment of these diseases was a lot less lucrative than, for example, specializing in surgery. With this in mind, it is not unreasonable to speculate that fewer people than would have been the case otherwise chose to be doctors. Government underinvestment can also partially be understood as a perverse outcome of the fear of oversupply. This also explains the fact that the region’s very few high-quality private hospitals tended to rely on foreign specialists; or simply flew out the few patients that could afford specialists abroad (a pattern that continues to this day).

Given the domestic supply/demand dynamics, it is odd that policymakers in a number of countries have been quick to scapegoat emigration as the problem. Banning doctors from leaving will likely not solve the problems of limited capacity in medical schools, lack of resources to train and remunerate medical professionals, weak demand for medical care beyond infectious diseases (although this is changing due to “lifestyle illnesses” and higher life expectancy), and the red hot demand for medical professionals in aging higher-income countries.

A better policy approach would involve creating functional domestic markets for the coveted skills of healthcare professionals. This means significantly expanding and increasing the quality of training; paying healthcare professionals reasonably high wages in addition to non-wage incentives (like mortgages, import tax waivers, etc); rationalizing public health sectors to make the referral system across tiers of hospitals better targeted; and incentivizing the expansion of high-quality private hospitals to share the burden of retaining medical professionals. Having high-quality hospitals in the region could also seed a medical tourism industry. That way the foreign patients would come to the doctors, rather than the other way round.

Blanket bans on emigration would not begin to address the real reasons behind the chronic undersupply of medical professionals in the region. Instead, the bans are more likely to keep African countries locked in a bad equilibrium of undersupply partially driven by structurally weak domestic demand. It would be better if policymakers saw external demand as an opportunity to expand supply to meet both domestic and foreign markets for medical professionals.

To be blunt, I don’t expect any of the countries banning the emigration of medical professionals to change course soon. I suspect that policymakers quickly resort to bans because that they are perfectly content running low-quality health systems that continue to be heavily subsidized by the gargantuan global health industrial complex. They also know that they can easily hop on planes to get specialized medical care overseas — someone should tell them the ability to pay for medical care in London is useless when you are having a heart attack in Lilongwe.

III: Exporting high-skilled services can benefit host countries

I have bad news for African policymakers who think that banning the emigration of high-skilled (medical) professionals will fix the problem. Research on emigration lifecycles suggest that the outflow of high-skilled professionals is only going to get worse with rising incomes in the region:

As GDP per capita rises, so do emigration rates. This relationship slows after roughly US$5,000, and reverses after roughly $10,000 (i.e. low- to middle-income, or the level of China or Mexico).

In the specific case of medical professionals, the high demand from aging higher-income countries will likely push their emigration numbers well above the overall average. It is odd that instead of seeing demand for high-skill services as an economic opportunity, many African policymakers have instead chosen the autarkic path.

The emigration of medical professionals is simply the export of high-skilled services. Like with most sectors, expanded global demand (which, in effect, exposes the domestic sector to global competition and associated standards) should be viewed as an opportunity for productivity and quality improvements in the the medical sector. For example, if there is high demand for Malawian nurses in the United States, nothing stops Malawian policymakers from thinking of funding options (or discussing the possibility of American funding) to expand and improve the quality of medical training in Malawi. Better training of more medical professionals would benefit Malawians who remain chronically undersupplied.

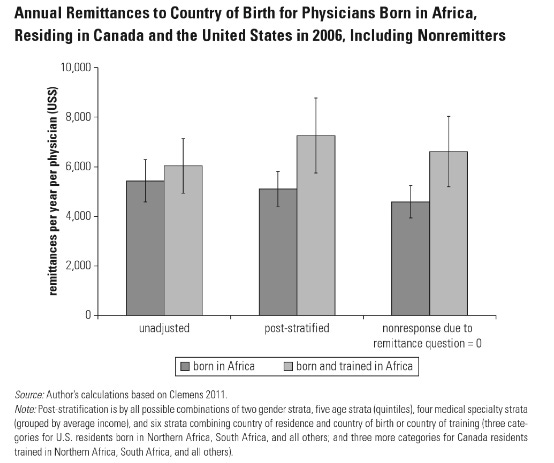

A skeptic may argue that Malawi-trained medical professionals who emigrate to the United States constitute a net drain on the Malawian economy. The evidence, however, suggests otherwise. Work by Michael Clemens of George Mason University shows that remittances from African doctors in Canada and the U.S. more than pay for their medical training back home. Conservatively, the typical doctor trained in an African country who then emigrates cumulatively sends home about 1.8 times the cost of their training. Notice that this is without any policy nudge (African embassies are notoriously for doing a poor job of keeping track of their professionals overseas). Furthermore, doctors born and trained in Africa send more remittances than doctors born in Africa and trained overseas. This factoid has implications for the emigration bans. If would-be doctors choose to train overseas as a result, their home countries would be willingly leaving money on the table.

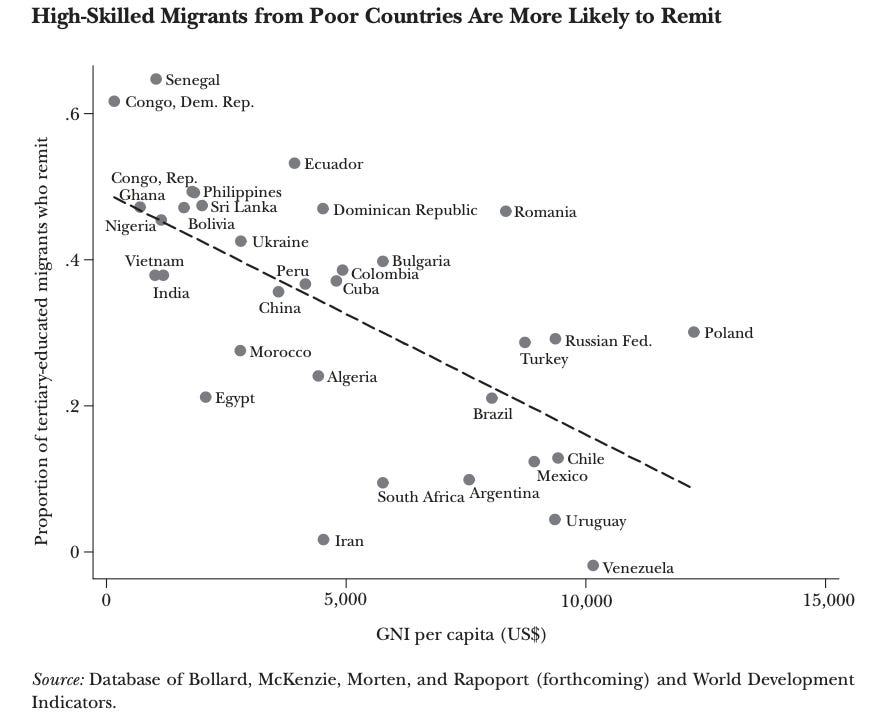

The fear that doctors would be “lost” to the suburbs of high-income countries is also misplaced. As shown in this review article, high-skilled emigres from low-income countries are more likely to send remittances back home.

IV: Conclusion

The idea of trained African medical professionals emigrating to high-income countries elicits all sorts of reactions. It is perfectly understandable that many view emigration as constituting a “brain drain” or the nefarious plundering of scarce skills in the region by high-income countries. However, I would argue that view only makes sense if one believes that it is actually possible to develop well-supplied and self-contained high-skill medical sectors in different African countries (and align elite incentives in service of the same). Since I don’t think it is possible to achieve this outcome, it is better to make policy that is robust to a world in which some high-skilled workers will want to emigrate. The fear that whole medical sectors will be hollowed out is misplaced, especially in the context of economic expansion and rising domestic demand for medical care in both public and private facilities.

Given all the factors at play, it seems like the reasonable policy response to potential emigration of medical professionals is to do a better job of training more of them domestically. Indeed, the more ambitious governments should consider investments in expanded and higher quality training as the first step in the direction of establishing medical tourism industries. For example, India runs a $7.4b medical tourism industry that attracts a non-trivial number of African patients — about 1.5 times the value of Nigeria’s non-oil exports.

Finally, governments should not shy away from addressing the equity concerns raised by skeptics of high-skill emigration head on. It is true that it feels icky for Malawi to be losing scarce professionals to the United States and the idea of the “brain drain” is easy to mobilize around. Smart policymaking should leveraging that ickiness to attract compensation from governments in high-income countries. In concrete terms, Malawi could ask for two forms of compensation from the United States: 1) U.S. subsidies towards the cost of training medical professionals (this could be indexed to the share of trainees that eventually emigrate); and 2) U.S. recognition of Malawian certification of medical professionals (and if U.S. medical industry lobbyists refuse to yield on this, Malawi should host any further residencies required before earning American certification — which should be paid for by the U.S.).

Regarding the African doctor remittances - surely the state is picking up the tab for the training and is not getting a slice of the returns? Or am I missing something?

I never thought about it that way: African countries should get a tangible benefit for exporting high skilled professionals. If a country wants to recruit young professionals from us: then they should invest in the country’s institutions. Thus, making this a win win situation