This is the third of three posts on African foreign policy under multipolarity. The first post outlines what ought to guide African foreign policy in a changing world; the second looks at how China ought to approach its Africa Policy; while this post examines potential opportunities to improve US (and Western) Africa Policy.

I: Sticky bad habits

More often than not, America’s Africa Policy betrays the persistence of sticky bad habits founded on 18th century ideas about Africa and Africans. The result has been decades of missed opportunities. For example, consider the glaring missed opportunity to leverage America’s large Black population to build strong relations with African states. Outside of Europe, no other region of the world has more built-in people-to-people connections through its diaspora that could be the basis of strong strategic alliances (America’s abhorrent history of chattel slavery and its aftermath matters, of course, but its effect on US Africa Policy was not determined).

Yet for decades America has merely externalized its prejudiced domestic racialist policies to the region, outsourced Africa Policy to former European imperial powers (and still largely does in francophone Africa), or dabbled in policies that left a lot to be desired (to put it mildly).

Even during the Cold War, when the threat of Soviet influence created incentives to build strong and mutually beneficial alliances, America chose the route of puppet regimes led by weak, unreliable, and geopolitically naive allies (notice that this fit the pattern of outsourcing policy to European neocolonialist ends). Intent on keeping its NATO allies on-side, America’s Africa Policy was about containing Soviet influence at all costs (not even allying with apartheid South Africa was beyond the pale). In practical terms this meant proxy wars, corrupting or compromising ruling elites, facilitating the pillaging of the region’s resources by multinationals in collusion with corrupt ruling elites, and a general neglect of countries that lacked obvious (Cold War) strategic usefulness.

It is a stunning consequence of this history that in a region of more than 54 countries, there isn’t a single country that readily showcases the economic and political benefits of being an American ally — at least not in the mold of Asian countries like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, or even Indonesia. The “shining lights” of state-to-state American friendship are misgoverned autocracies that benefit from large amounts of military aid. While the wanting quality of African leaders over the decades explains much of this failure, it is also fair to say that the US (and its European allies) played a role in selecting/supporting pivotal African leaders during the same period.

The rise of China as a major global power in the 21st century has awakened America’s strategic interest in the region. However, America’s reaction to Chinese competition in Africa remains shackled to the same old sticky bad habits. Policymakers in Washington have struggled to see forging alliances with African countries as ends in themselves, instead seeing the region merely as a means to and end. Countering China, like it did the Soviets before, is still the dominant motivation.

One of the pernicious effects of the history outlined above is reflected in personnel. Given the shockingly horrendous Africa content in American school curricula, media, and entertainment, a specific type of American self-selects into cultivating an interest in the region. While there are many smart people with a balanced understanding of Africa working the Africa Desk in various US agencies, their noble efforts are typically swamped by the sticky bad habits of colleagues both within and outside the Africa Desk. Too often, the people who ultimately shape Africa Policy are single-issue activists interested in genocide, civil wars, famine, or democracy promotion — and who are mostly motivated by the “Otherness” of hapless Africans in need of saviors.

Such policymakers, however bright and well-meaning, have blinkers that prevent them from seeing the region beyond its problems and their imagined causes. The same goes for American academics who study and reinforce the rich repertoire of misguided “stylized facts” about the region. It is therefore not surprising that American foreign policy has historically been dominated by a very narrow understanding of African countries and shallow engagement on a limited set of domains including security, natural resource extraction, humanitarian assistance, public health, and democracy promotion. Not even the new era of “evidence-based” international interventions offers much hope.

All this to say that it will take a lot of deliberate effort to cast aside the sticky bad habits that continue to hobble US Africa Policy. Importantly, it will require a change of personnel — from those who view Africa as a simple problem to be fixed (forget the decades of failure) to those that understand the region in its full complexity.

II: Rethinking US Africa Policy

At this juncture I should note that despite the failures outlined above, there have been some bright spots in US Africa Policy. President George W. Bush’s PEPFAR initiative saved countless lives in Africa and beyond. Despite being hobbled by its eligibility criteria (which get in the way of building strategic long-term relationships), the Millennium Challenge Corporation has potential to foster strong US commercial relations with African countries. Other commercial initiatives like AGOA, US African Development Foundation, the US EXIM Bank, USTDA, OPIC/DFC, and Power Africa have also had varying degrees of successes (often conditional on the seriousness of US personnel and African partners involved).

I should also note that there are reasonable Africans who question the utility of even considering a constructive engagement with the US given its history (and that of its European allies) in the region. While I understand their misgivings, I still think that America can be a useful partner in African political and economic development. This is for two reasons: 1) the fact of the matter is that the US is still the preeminent global economic and military power with lots of cash, a large market, superior technology, and the best research universities; and 2) there is reason to believe that the US is open to learning from past mistakes in an effort to improve US-Africa relations. Therefore, it would be foolish for African countries to not push for change in the right direction, albeit without forgetting the lessons of the past.

Overall, I tend to think that both the US and African countries stand to benefit enormously from a deepening of US-Africa relations. I am eager to track the implementation of commitments made at the recent US-Africa Leaders Summit. In an earlier post I shared my thoughts on how African countries ought to engage the world (including the US). Below I provide some suggestions on how the US can improve its Africa Policy.

Internalize the fact that strong states make for strong allies

One of the most important geopolitical lessons from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is that it pays to have strong allies. Without a capable government in Kyiv with a valiant military, NATO would have struggled to constrain Russian adventures in Ukraine. The same cannot be said of many African countries that are nominally allied to the US or its NATO partners. For example, across the Sahel governments barely have control beyond their capitals and remain vulnerable to armed groups of young men with little more than motorbikes (or technicals) and AKs.

The same African governments have, for decades, failed to provide the basis for prosperity for their people, further fueling conflicts and unimaginable levels of human suffering. And as noted above, the US and its European allies bear some responsibility for the fumbles by post-independence African governments in their initial state-building efforts. From the mining of uranium in Niger, to oil in Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and Nigeria, to the vast mineral riches of the DRC, partnership with America and its allies have yielded little to celebrate.

To correct course, a core priority of American friendship ought to be to help its African allies in their state-building efforts. By state-building I mean both the (at times violent) monopolization of the use of force and capacity to provide essential public goods and services (what some scholars refer to as “inward conquest”). This is not a call for an American-led state-building (we all know how those tend to go). Rather, it is a call for genuine partnership with would-be state-builders whose interests (by construction) may not always align with those of the US or its European allies.

****

It is better to have dependable strong allies capable of standing on their own feet even if it means the occasional disagreement, than kleptocratic puppet regimes that run of out town at the first sight of insurgents and who cannot deliver on the most basic duties of any government. Stated differently, a friendship founded on (exploitative) structural subservience and co-dependence is not a real friendship.

****

Stronger African states would provide the basis for improving African livelihoods by reducing the incidence of civil wars, insurgencies, and generalized elite political instability. They would also obviate the need for costly direct American military interventions in the region.

Prioritize support for African growth and development

In the spirit of cultivating dependable strong allies, America should prioritize support for African states’ developmentalist agendas. This means foregrounding commercial relations — especially support for agriculture, infrastructure development, manufacturing, and trade. The US government can do this both through direct programing and by leaning on its private sector using policy incentives. For example, to mitigate the overblown “risk” perceptions of African economies by American firms, it can provide investment guarantees for a finite duration of time. America can also lean on the IMF and the World Bank to reorient their mission towards proactively supporting African development (instead of mostly being standby firefighters and/or marginal reformists).

One of the oddities of US-Africa relations is that despite the tremendous growth that African countries have witnessed over the last two decades, trade with the US has actually declined over the last decade from their peak in 2008. This, in my view, is primarily due to policy failure on the part of both African and American governments. For example, given the size of its market for battery metals, there is no reason why the US did not proactively take a constructive leading role in the creation of value chains for African minerals critical to the green economy.

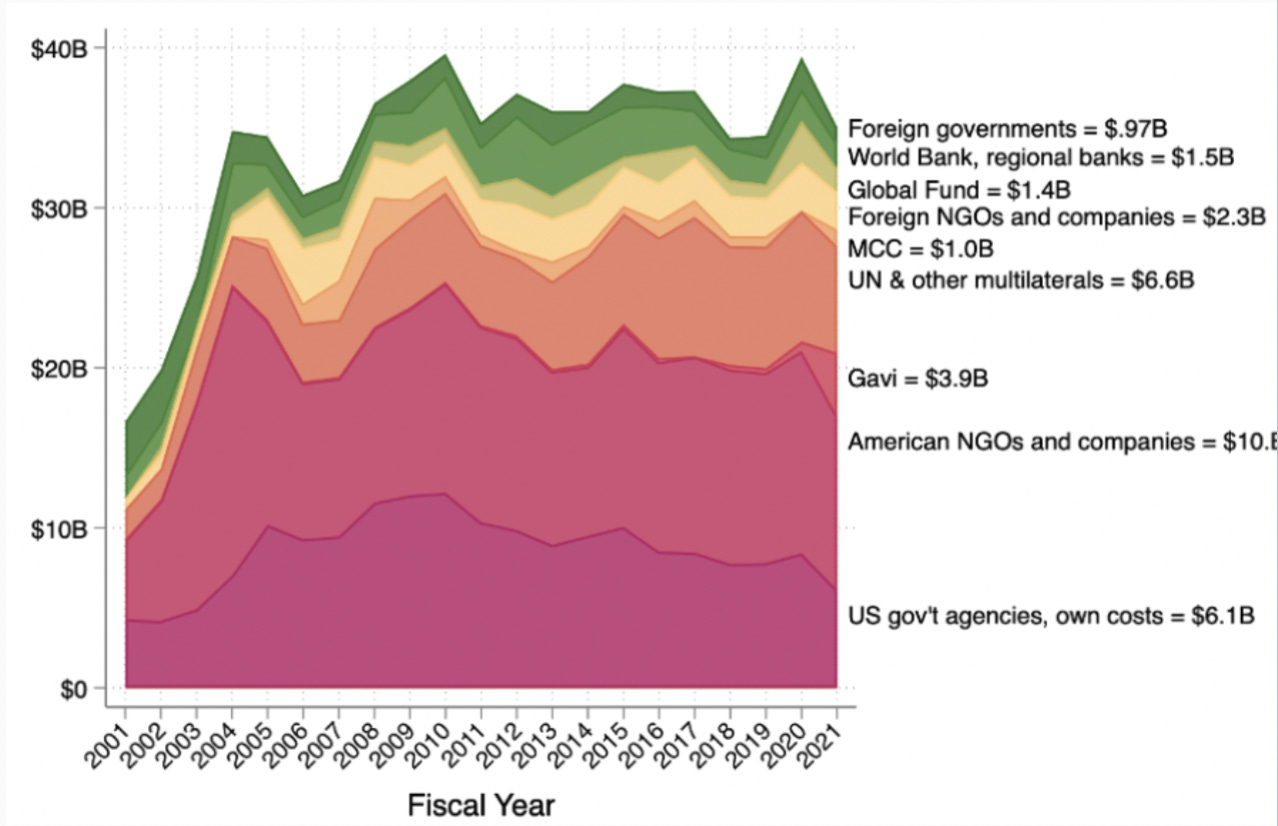

The nature of American assistance is another strong case for doubling down on stronger commercial relations (instead of aid and humanitarian assistance). Much of American assistance to African states takes the form of inefficient tied aid (i.e., targeted to pay American workers, farmers, shipping companies, defense contractors, etc) with questionable real impact on the ground. In other words, America helps by mostly overspending money on itself (see above).

No reasonable person would view this as a recipe for transformational economic change in Africa. I am not one to rubbish all forms of aid. When properly designed and targeted, aid can help communities get back on their feet after war, natural disasters, or macroeconomic collapse. However, the aid industry as currently structured will never catalyze real economic transformation in Africa.

Streamline the objectives of US Africa Policy

The US government often works at cross purposes in African states. It is not uncommon to find democracy promotion efforts by USAID, IRI, and NDI getting diluted by the DOD’s security assistance to autocratic incumbents in the same country; or US-funded governance reforms getting sidelined by American multinationals’ lucrative “incentives” targeted at corrupt incumbents.

Admittedly, part of the problem arises from America’s sheer size and the need to attend to multiple conflicting constituencies — such voters who want to see the US “do good” in the world, elite policy constituencies with specific ideological commitments, policy capture by international development experts, campaign donors with specific commercial interests, and the concerns of the national security establishment.

That said, given that the White House retains significant discretion over foreign policy, it ought to be able to streamline US Africa Policy — preferably in favor of prioritizing commercial relations and support for African states’ developmentalist agendas. This is not to say that the US should abandon all other issue areas. It is simply a call to have a clearer ordering of priorities (with commercial relations on top) and communicate the same to all relevant agencies.

Align US Africa Policy (and rhetoric) with African Institutions

Pan-Africanisms is a strong driver of foreign policy in Africa. From the various regional economic communities (RECs) to the African Union (AU), African states have historically relied on regional bodies to amplify their actions on the global stage. Pan-Africanism is also very popular with African middle classes and opinion-makers.

America stands to benefit from aligning its Africa Policy with the organizational architecture that structures intra-African relations. For example, any bilateral security pacts should not erode the spirit of the African Union’s peace and security architecture. Similarly, bilateral trade deals that go against the spirit of the AfCFTA or REC-level commitments will likely be viewed as nefarious by the rest of the region (and a continuation of the sticky bad habits of old).

Given that America does not have the bandwidth to be built deep bilateral relations with all 54 sovereign African states, both the AU and RECs provide opportunities for constructive engagement with strategically important “anchor” nations that can showcase the benefits of being an American ally — ideally modeled around broad-based economic prosperity, political accountability, and capacity to project power and influence (within the AU and respective RECs) in service to overall regional security and stability.

Cultivate a strong pro-Africa constituency in the American electorate

The history of American diplomacy suggests that it is very hard for the United States to have a consistent foreign policy agenda without the support of a strong domestic constituency. Presidents, Congresspeople, or specific agency officials come and go. But organized and vocal voting constituencies are forever.

Despite having a large African diaspora (about 47m), American politics lacks any organized pro-Africa lobby or voting constituency. This means that much of Africa policy tends to be driven by specific officials or politicians with personal ties to the region. It also means that attention to Africa waxes and wanes with every election.

A White House that is serious about its Africa Policy would embark on a political education campaign to convince the American electorate of the usefulness of strong relations with African states. American presidents can mobilize public opinion in support of their foreign policy agendas. While the large African diaspora would be a natural starting point, such efforts would also include any and all constituencies that stand to benefit from better US-Africa relations. A strong pro-Africa constituency in America would in turn serve as the basis for strengthening people-to-people relations and cultivating pro-America sentiments among African electorates.

III: Conclusion

Contrary to received wisdom, Africa will not always be a geopolitical backwater. The world’s demographic future lies in the region. Its economies are showing signs of takeoff and present lucrative opportunities for would be commercial partners. And its challenges are global.

The current moment presents an opportunity to seriously rethink US-Africa relations. It is high time America abandoned the anachronistic views of Africa and Africans that continue to influence its Africa Policy and saw the region for what it really is.

I have argued that such efforts will require support for state-building in the region, prioritization of commercial relations, rationalization of US Africa Policy across agencies, alignment with African institutions, and cultivation of pro-Africa political constituencies in the United States.