Is `Global Development' dead?

The case for optimism on the possibilities for economic expansion and continued improvements in human welfare

There is much food for thought in a piece by David Oks and Henry Williams over at American Affairs on the “slow death of global development” (including in Africa).

I do not endorse all the claims made in the piece (see below). However, I hope that academics and practitioners working in the field of international development read it and think carefully about its core claims. In my view, the authors present an important critique of current development research and practice.

The piece’s main weakness is that it downplays several positive changes that have taken place in global development over the last four decades. By focusing on the failures of the Western “global development” establishment, the authors ended up missing the realities of economic change since the 1980s in much of the developing world as well as potential paths to future prosperity .

I: On the alleged death of global development

The piece starts with a general critique of the fetishization of measurement and rigor in the study of developing countries’ economies — which by eliding countries’ histories and politics, distracts leading minds (especially policymakers) from correctly identifying and tackling the structural barriers to transformational economic development in low-income states:

We do not seek to simply make a pessimist’s case for why economic development has not occurred, or why various statistical flaws mean that we should disregard undeniable progress in reducing global poverty. Rather, we aim to show why the prognosis for the poor world is much worse than the standard picture—preoccupied with a purely quantitative account, however rigorous, and ignorant of more geographic, historical, and political-economic approaches—has allowed; to explicate the structural changes that have undergirded the perverse trajectory of global development; and to outline a more realistic outlook, married to a new framework, for a return to real development.

This is not a case against measurement and analytical rigor, per se. Reasonable people understand that the credibility revolution in empirical research heralded an unambiguous improvement in the social sciences. However, policymakers should internalize the fact that the vast majority of academic researchers are poor at policymaking; and are primarily interested in publishing and advancing their careers. To be blunt, an uncomfortable share couldn’t care less about the political/institutional intricacies of policy implementation in a typical low-income country. It follows that academics’ rigorous studies (however great they may be) are poor substitutes for serious context-based and politically-relevant policy research in developing countries (more on this in a future post).

For example, academics are definitely within their rights to rigorously study and debate in seminars whether feeding children in school really causes an improvement in test scores. Policymakers, on the other hand, should spend their time and resources figuring out how to FEED ALL THE KIDS within their jurisdiction. Any policymaker who, in the name of being rigorous feigning ignorance, asks for evidence that feeding kids is a good idea should be out of a job.

The piece then goes on to identify the crux of the problem with global development: the fact that many low-income countries are seeing a simultaneous shrinkage of their industrial and agricultural sectors:

The crux of the problem is this: despite attempts to find alternative models of economic development, there is no widely replicable strategy to develop a country—simply put, to turn it from poor to rich—that does not involve an economy becoming highly industrialized. But in recent decades, the growth of manufacturing sectors, and thus of economic development more broadly, has been overwhelmingly concentrated in East Asia, particularly in China. Across the bulk of the poor world—here we have in mind Latin America, South Asia, the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa—economies have been experiencing a more disturbing trajectory: simultaneous deagrarianization and deindustrialization, especially in the years after 1980.

This is an important observation, especially with regard to the agricultural sector (more on industrialization below). The ongoing deagrarianization in Africa, the result of a criminally negligent policy failure, should be getting a lot more attention than it currently does. Notably, the movement away from agriculture is not being driven by improvements in productivity (not even in the cash crop sector). What this means is that ever more people in the region are becoming food insecure and/or exposed to fluctuations in global food prices (not to mention the macroeconomic effects of states’ use of scarce forex on food imports).

Oks and Williams also discuss the problem of “premature financialization” in low-income societies that is common in current development practice:

In Brazil, the household debt-to-income ratio rose from 18 percent in 2004 to 60 percent by late 2021. This “premature financialization” of poor-world economies often takes on a highly predatory character: pyramid schemes have enjoyed remarkable growth in African and Asian countries in recent years, with unemployed and underemployed youth a perfect target. One 2017 study found that 70 percent of Nigerian students had bought into at least one pyramid scheme. The popularity of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum in these countries is a product of the same dysfunction: early Bitcoin adoption in Africa, in fact, was driven by the pyramid scheme company MMM—which had first found large numbers of victims in Russia during the agonies of the 1990s.

Notice that the premature financialization (with all its good and bad effects) in Brazil and other contexts is partially attributable to an ideational shift by development experts and policymakers away from structural economic transformation to individual-level or household-level interventionism in the fight against poverty. It is worth noting, as economic anthropologists have over the past two decades, that this shift came with real costs for low-income individuals and households.

Having pointed out several pitfalls of current approaches to the question of development, the piece argues that the way forward should pass through deliberate state-building, cultivation of developmentalist political coalitions, and agricultural modernization. These are all important priority areas. Finally, the authors remind the reader that salvation won’t come from the current “development community” and its leading experts:

What then, given the concurrent necessity and impossibility of industrialization in the poor world, particularly in Africa? The reality is that Western elites do not have an answer. They have not forged a new developmentalism that they can offer the poor world in the aftermath of global deindustrialization. In the absence of a new paradigm, they can furnish new RCT studies or occasional colloquia with development experts. But for all their obfuscation, it is the blind who are leading the blind. Indeed, the intellectual exhaustion of the elite “development community” is hard to fathom. In its upper echelons, those who still believe in the hoary orthodoxies of past decades—free trade, democratization, the extraordinary importance of what are nebulously referred to as “inclusive institutions”—coexist uneasily with more humble types who will admit, in private, that they have no real answer at all.

As noted above, there are glaring gaps in some of the arguments in the piece (see below). However, it is also an important exercise in truth-telling about the emperor’s clothes in the field of international development (the strong Coming Anarchy undertones notwithstanding).

II: Are things really that bad?

I would argue not.

It’s true that the field of international development is not working as it ought to. Too much time and resources get wasted on faddist navel-gazing instead of serious investments in knowledge production and policy focus on structural change. Policymakers in donor agencies and developing countries are too easily distracted by the next shiny thing (including ill-suited claims of rigor). Due to the over-reliance on “apolitical” foreign expertise with no skin in the game, much of development thinking ends up erroneously assuming that poor countries are poor because their policymakers/politicians are dumb/autocratic/corrupt. Consequently, many low-hanging potential wins get neglected simply because they are boring or don’t fit within the orthodoxy espoused by experts.

That said, it is simply not true that there’s been nothing but four decades of stagnation or decline in developing countries as alleged by Oks and Williams. Just because structural economic change doesn’t get much airtime in Western academic/practitioner circles does not mean that it is not happening. The last 30 years have seen significant improvements in the developmental outcomes in many low-income countries, including in Africa. From infrastructure, to education attainment, to life expectancy, the last three decades have witnessed real economic change in most African states.

Before the disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, Africa as a region clocked 25 years of uninterrupted economic growth.

I emphasize these facts because it is absolutely important that African policymakers internalize the right lessons from the region’s economic history over the last 60 years. As Thandika Mkandawire and Morten Jerven remind us, the narratives we tell ourselves about economic history matter. A sweeping dismissal of the gains of the last four decades is a recipe for failing to appreciate the region’s economic successes and to build upon them. Indeed, it is the failure to learn the right lessons from economic history that fuels the intellectually anemic and inherently whimsical approach to international development that the authors rightly critique in their piece. The idea of perpetual stagnation in Africa (and elsewhere in the developing world) is a myth that needs to be put to rest.

III: A tale of two graphs (do not compare me to the almighty)

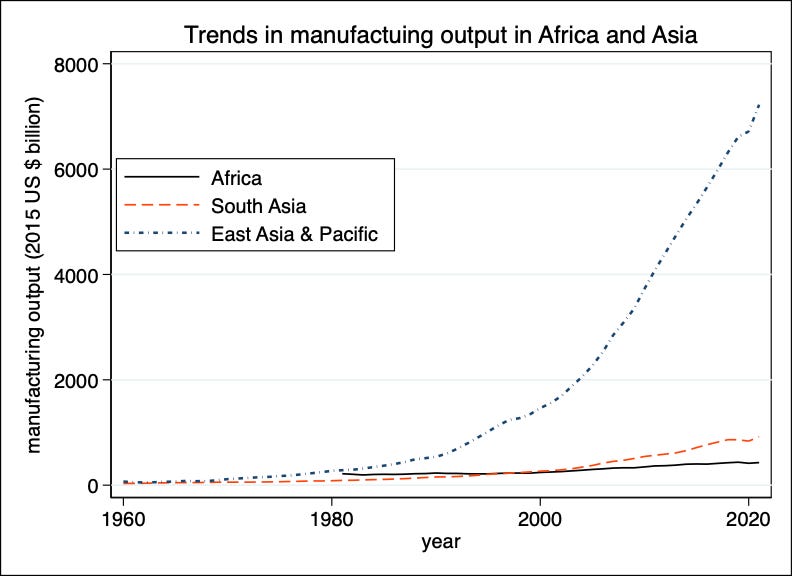

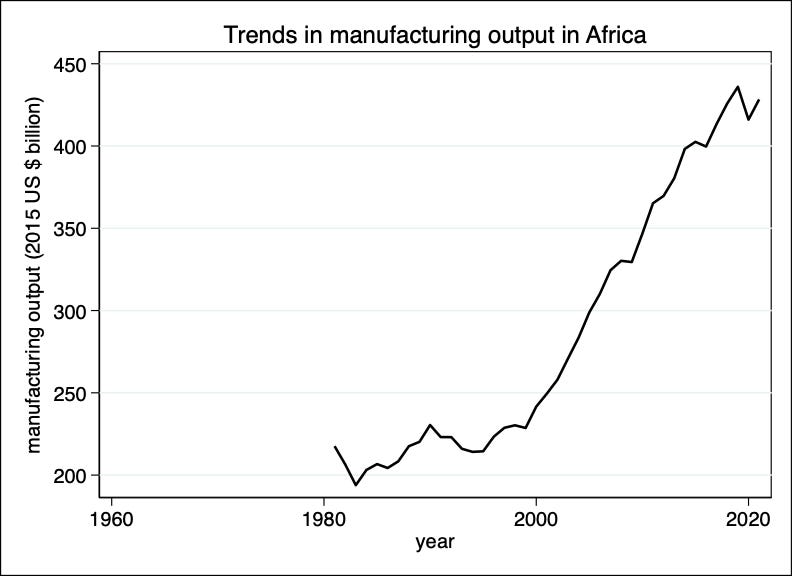

Consider the example of manufacturing output. The narrative the authors present is that not everyone has done as well as China over the last four decades. This is true (see Figure 1). It also doesn’t present the whole picture (see Figure 2). In Africa, for example, the total value of manufacturing output has more than doubled (in real terms) over the last 20 years. Yes, manufacturing is concentrated in a few countries and does not even begin to create enough jobs for Africa’s young people. Furthermore, high labor costs and poor infrastructure continue to be real barriers to continued manufacturing expansion. But it is one thing to highlight and attend to the barriers to competitive manufacturing in Africa, and quite another to essentially claim that manufacturing is not possible in the region — especially when the evidence shows that it is.

No reasonable person would dispute that African countries are far from optimal levels of manufacturing output. However, it would be a mistake to dismiss the changes seen since 2000 as inconsequential. Doing so runs the risk of reinforcing the idea that manufacturing is not possible in the region.

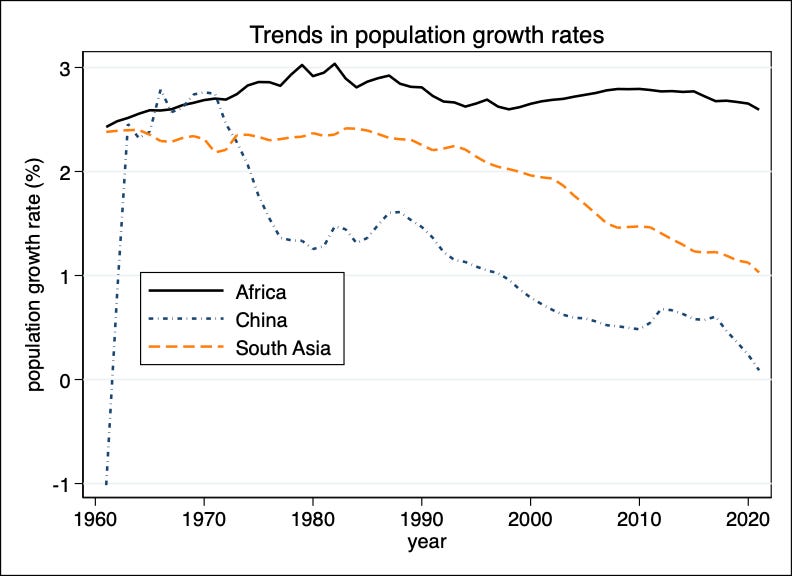

The other structural factor that the authors fail to appreciate relates to demographics. Between 1960 and 2021 China’s population increased by 2.11 times. Over the same period South Asia’s population increased by 3.3 times and Africa’s by 5.2 times. While the authors discuss population from the perspective of contemporary surplus labor and joblessness, it is also important to note that dizzying population growth rates over the last six decades tempered the growth of per capita income in Africa and South Asia. As Johan Fourie argues, the (relatively) high population growth rates in African countries have masked the impressive growth rates between 1960-1980 and 1995-present. Therefore, any summary judgement over the region’s economic performance that does not appreciate its dependency ratio is simply incomplete.

Finally, the authors discuss the connection between state weakness and development. Here, too, the analysis could have benefitted from a temporal understanding of political development and state-building in African states. Part of the reason why the crises over the long decade between 1980-1995 were especially destructive was because they could not have come at a worse time. African countries were barely 20 years old, and still very much trying to figure themselves out. 40 years later, things are different. And so while weak states still dot the region and nearly all states struggle to project power throughout their territories, it is also true that the typical African state is a lot more consolidated today than it was in 1980. That counts for something. More importantly, it means that the past will not be that good of a guide on how African states will respond to current and future crises.

IV: Conclusion

Transformational economic growth and development are possible in Africa. Contrary to popular belief, the crises between 1980-1995 are not the definitive elements of the region’s economic history. There was real growth before (1960-1980) and after (1995-present) that produced tangible developmental outcomes. A narrative of stagnation simply does not match the facts. In the same vein, highlighting the blindspots of global development need not lead to unnecessary catastrophizing about Africa’s future economic prospects.

I’m afraid I still find the case for a deep cynicism on African development convincing.

If the crises of the 80s came at a particularly vulnerable time for most of the continent, the ongoing wave of mercantilism and deglobalization may prove no less inopportune. Virtually no African states put the era of cheap credit and global markets that’s now ending to any use except to get foreign companies to export their raw commodities. I’m not at all convinced we’ll navigate the much rougher seas ahead with any more skill: many countries likely already have their best years of growth behind them. Much of the continent will be locked out of future regional manufacturing supply chains, and with the advances in automation taking place there couldn’t be a time when a massive labor surplus would be less of an asset. We’re simultaneously being cut out of the renewable energy revolution and losing access to financing for fossil fuel projects except for export.

Even assuming these states had workable development plans, there’s been a eye-watering interest rate hike that may not come down for a long while. Governments are accessing credit on usurious terms. That means very little investment, foreign or domestic, will be possible on any of our most pressing needs. We’re already seeing signs of another 80s style spate of sovereign defaults, except in a more ambiguous, more hostile international environment. The limited gains made in food security, education and healthcare are stalling and all now risk being unraveled.

As for African states being more coherent or resilient, I’d argue some have learned to maintain appearances better but are still hollow. Looking around, Ghana and Zambia are in default. Kenya is stagnating, and will likely soon follow them into bankruptcy. Egypt is in an IMF straitjacket, and won’t get out without reining in its military, which seems unlikely. Nigeria’s economy is in bad shape and it still hasn’t got a grip on its security situation. South Africa can’t even keep the lights on. Whatever momentum Ethiopia gained in the last two decades was lost in Tigray. Sudan will probably be a war zone for another fifteen years. The DRC is too lucrative to too many parties to ever be stable. Rwanda is growing, but too small and starting from too low a base to make a difference to the overall picture.

Zooming out, the entire Sahel region is imploding, and the free flow of weapons and fighters means this probably cannot be arrested even in the medium term. The AU is moribund and too easily bounced by external actors to be a meaningful force. Regional integration isn’t happening with any of the urgency required. The AfCFTA is making very little progress. Our geopolitical prospects may be improving, but that just increases incentives for elite subversion. Imperial powers old and new are tightening their hold on their interests. The current crop of leaders is as spineless and short-sighted as any before it, and it doesn’t look like the next is up to the job.

An instructive reference point for me has been India: its fundamentals are incomparably ahead of most of Africa yet I still would predict a long and uncertain path to relative prosperity for it. Even China arguably hasn’t completed its development, miraculous as its rise has been. I find it very unlikely a substantial proportion of the continent will experience strong enough growth to achieve reasonable average living standards before running into demographic headwinds. Birth rates aren’t plummeting as sharply as Asia but they’re still dropping fast, and Africa may hit its peak population in as little as 20 years. The time to get our act together is running out fast.

I agree that a bright future can be achieved. But I think it’s also important to acknowledge that right now our prospects are bleak, and to sit with the possibility our grandchildren may never know prosperity. A positive outlook in the face of adversity has to be wed to a dispassionate view of our situation if we are to have a chance at meeting the challenges ahead. Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will, as Gramsci put it.

Nice piece grounded in reality, i am Nigerian living in Nigeria and i can say that the picture that the west and their academics paint about Africa is not accurate, just within the last 5years we have produced 5 startup fintech companies valuated more than a billion dollars(e.g. Flutter wave), and we have a very high number of female entrepreneurs.