In Africa, Russia is playing the West like a fiddle

Putin is the proverbial small man who casts a large shadow

Nearly all of An Africanist Perspective is free content. In addition, there is revealed demand for content on topical issues in the headlines — like what I cover in this post. These “current affairs” posts are gated and only accessible to paid subscribers. Paywalls will come down a month after gated posts go up.

I: A small man casting a big shadow

Over the last four years it has seemed like the biggest geopolitical investment Russian president Vladimir Putin could make in Africa was to buy a cheap flag making business. More than Russia’s actual military and economic footprint in African states, images of a few people waving Russian flags during protests in Bamako, Bangui, Conakry, Niamey, or Ouagadougou have been enough to elicit all manner of alarmist reactions among a significant section of Western journalists, security analysts, and policymakers.

Simply put, there is a wide chasm between Russia’s actual ties and influence across Africa and the hype one encounters in the Western media and policy outputs. For several years Russia’s total trade with Africa — at about $18b (under 3% of total) — was relatively small, declining, and concentrated in four countries (Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, and South Africa) that account for 70% of the total. Egypt alone constitutes about a third of Africa-Russia trade.

Since invading Ukraine, Russia has sought to increase the region’s share of its total global trade above the current 3.7%, with specific attention to increasing African primary commodity exports to Russia. However, African exports to Russia still make up a tiny 0.4% of the region’s total exports. In addition, Russian foreign direct investments in Africa amount to about 1% of the total flow. These numbers are not what one would expect from an alleged geopolitical heavyweight that is supposedly about to remake the region’s alliance terrain.

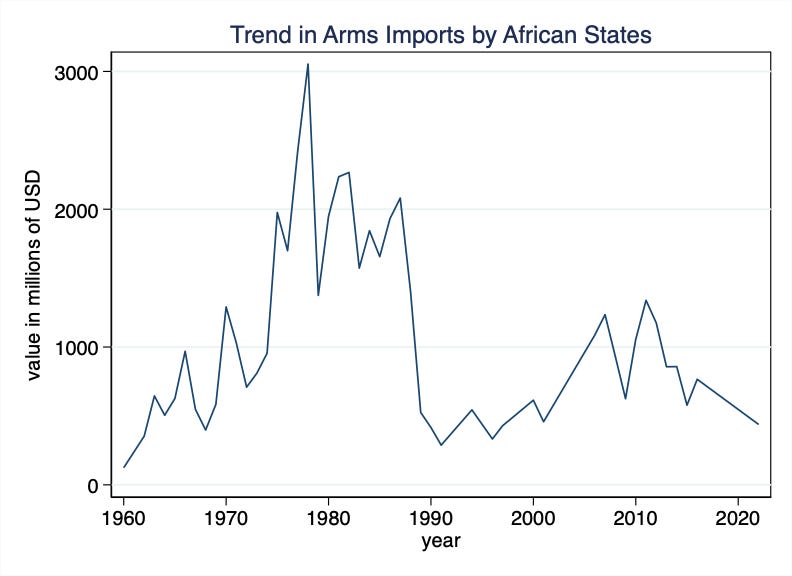

While Moscow is a leading arms supplier to a number of African states — a fact that is often cited a multiplier of its influence in the region — the actual numbers are inarguably underwhelming. Earlier this year SIPRI, a Swedish tracker of conflicts and trade in arms, noted that Russia had increased its share of weapons supply to Africa to 26% of the regional market share. The report was greeted with the usual willfully ignorant shock and alarm. Yet the figure quickly loses its punch once one realizes that it represents less than $115m in flows to a region of 54 sovereign states. Arms sales in Africa simply aren’t what they used to be (see below).

Not even the footprint of Russian private military contractors in the Central African Republic (CAR), Burkina Faso, Libya, Mali, and elsewhere offers much to sing about. These countries/armies went to Russia out of desperation in the face of armed insurgents and (in some cases) sanctions that limited their ability to access arms on the global open market (see below). In other words, their relationships with Moscow can barely be described as founded on solid ground. Indeed, these countries’ levels of internal instability mean that their regimes remain vulnerable despite Russian support — you can only go so far with petty smugglers and violence entrepreneurs with limited ambition. Importantly, the vulnerable Russia-dependent countries are far from being influential in either Addis Ababa or within Africa’s Regional Economic Communities (RECs).

From an African perspective, there simply isn’t any evidentiary basis for believing that African states would have any reason to tie themselves en masse to Russia as the strategic major power ally. Those in doubt should review the attendance register during the 2023 Russia-Africa Summit or read up on African reactions to Russia’s abandonment of the UN-brokered grain deal. In any case, it should not come as a surprise that a region with 54 sovereign states would include a few countries that found the need to be strong allies with a revisionist power like Russia. And when it comes to civilian trade relations, African countries have no apologies to make for trying to access vital imports at the cheapest prices on the global market — especially at a time when elevated inflationary pressures and fiscal constraints leave them with little room for maneuver.

Without paying attention to these specific realities of African economies and the incentives their leaders face, empty moralizing about “values” and the need to isolate Russia will not work — especially when there is ample evidence on how G7 and EU economies strategically took their time to fully decouple from the Russian economy. It doesn’t require special insight to understand that much-poorer African states also require time and an expanded (and funded) menu of viable options in order to make similar shifts. The circular-referencing loop that is much of the Western commentariat may not be bothered to read news from African countries, but they should always operate under the assumption that Africans consume copious amounts of Western news. They know all about the accommodations that NATO members and their close allies got in anticipation of sanctions against Russia.

All this to say that it makes little sense to solely evaluate Africa-Russia relations from the perspective of Russia as puppet master. Instead, the point of departure should always be that African states are pursuing specific interests that on some occasions converge with Moscow’s. For example, Egypt and Ethiopia want arms and grain. South Africa wants to side with a BRICS ally that shares its revisionist ends, in addition to standard trade-related interests. The Central African Republic needs to keep its president alive and avoid having the entire country overrun by insurgents. While Russia also benefits from these specific instances of convergence of interests, the reasonable response from its competitors ought to be to give African states better counter-offers. It is irrational to expect African countries to sacrifice their own legitimate interests in service to an international system that for decades has firmly kept them them in the periphery.

II: Why are so many Africans receptive to Moscow’s grievances?

Given the relatively small strategic importance of the two-way relationship between African capitals and Moscow, Putin’s success in rattling the West in Africa is predicated on two factors that reinforce each other.

First, Russia has astutely exploited age-old Western attitudes towards Africa and Africans — especially the refusal by much of the Western commentariat to imagine, let alone accept, that African states and their peoples can ever have legitimate interests of their own and exercise agency while conducting their international affairs. The failure to internalize the notion of African agency means that Western journalists, analysts, and policymakers are likely to view African states’ foreign policy positions not as expressions of interests, incentives, and politics, but as the results of being hoodwinked by Russia (or China). In the same vein, they are likely to completely ignore or downplay the manifestations of Western policy failures in the region (see below), a fact that reinforces African public perceptions of the West as singularly interested in domination and not much else.

Second, Russian analysts were well ahead of the West in appreciating the potency of sovereignty as a mobilizing force in contemporary Africa. No systematic works exist to explain why sovereignty has become particularly salient now, but possible explanations include recent widespread discussions of decolonization and African states’ sovereignty gaps (and the memeification of the same for mass audiences). Increasingly overt great power competition may have also played a role in reminding everyone of possible alternative orders that grant their countries more agency in their own affairs. With this in mind, it is not a surprise that in 2023 Russia’s revised foreign policy concept explicitly noted that Moscow would prioritize the protection of African states’ sovereignty and position in global affairs.

While Western analysts purely saw this as Russia’s disingenuous face-saving propaganda in the wake of its illegal invasion of Ukraine (which it partially was), the information wars accompanying it tapped into and resonated with African publics’ legitimate grievances — especially in countries that had endured decades of stunted political and economic development due to French neocolonialism. There is a reason why trust in Russia tends to be relatively higher in former French colonies.

Under the circumstances, it often seems like all Russia has to do is make a viral clip of Emmanuel Macron echoing racist colonialist tropes or Giorgia Meloni disingenuously covering for Italy’s atrocious immigration policies by condemning French (neo)colonialism in Africa. By ignoring legitimate African interests and incentives, the Western response to Russian material/informational influence operations invariably bolsters Russia’s favorability position. This, in turn, reinforces Moscow’s ability to achieve convergence of interests in the region on the cheap (see trade and FDI flow figures above).

In Sahelian streets disaffected jobless youth have waved Russian flags, not to express a love for Moscow or Putin, but to indictment an international system and their venal elites that has kept them in a neocolonial chokehold for decades. The same sentiment is evident in WhatsApp groups in polite society, where it is often expressed in more intellectualized form. Either way, the net effect is the same: across much of Africa Russia has become a useful foil for making the case for reforming an unfair international system and beginning to conversation about meaningful African sovereignty. Several African states have expressed similar sentiments in international forums with their insistence on neutrality vis-a-vis Russia’s war on Ukraine, while also defending the principle of sovereignty and sanctity of state borders (notice that they are not the first countries in world history to hold contradictory positions in pursuit of their interests).

III: Reckoning with potential African policy mistakes regarding Russia

If we accept that African countries have a right to make their own foreign policies, we should also expect that they will make mistakes. After all, history is full of colossal foreign policy failures by much better run states that cost millions of lives. There is a difference between making wrong policies due to domestic or international political/economic constraints and being the perfect puppets of Big Bad Russia. The African countries that have moved closer to Moscow over the last decade largely fall in the former category. Importantly, the quality of African leaders espousing sovereigntist rhetoric, the type of regimes they lead, or the level of coherence of their policies are not justifiable excuses for roundly dismissing their countries’ right to sovereignty. The messengers may be imperfect, but they carry a legitimate message.

Reasonable people would agree that relying on foreign states’ military or private contractors is not the best way to create a well-ordered society. Whether it is drones raining fire on villages from the sky in Somalia or military contractors killing civilians in the Central African Republic, foreign armed actors are less likely to fully internalize the domestic political and social implications of their actions. Furthermore, their mere presence creates strong disincentives against meaningful investments in state-building and conflict prevention/resolution.

The point here is that African countries ought to learn the right lessons from the last 60 years regarding an over-reliance on foreign military or civilian guarantees that undermine domestic sovereignty.

Besides arrested state-building, African countries that grow close to Russia also risk getting stuck in an economically stagnant defensive club of perpetually aggrieved revisionists, a fact that would likely limit their ability to build alliances with all manner of countries with a view of promoting trade and investments in their economies. Letting the relationship with Russia grow from one of tactical convenience to Moscow becoming an indispensable patron would be a mistake. With a shrinking population and an economy that does not have that much dynamism outside of mining, agriculture, and arms, Russia does not offer much in terms of future economic promise.

For those forced into working closely with Moscow, Russia can be a useful source of leverage in efforts to reform the international system and related institutions of global governance. But even as they engage Russia African policymakers should never mistake means for ends. The end should always be to establish meaningful African sovereignty and the betterment of Africans’ material conditions.

Overall, African states will avoid the pitfalls noted above by remaining singularly focused on serving their population’s material interests. Their true friends will make the effort to know those interests, the specific incentives that policy elites face, and then seek to find points of convergence. Those not bothered to do their homework or take African interests seriously should be roundly ignored. Obviously, pursuit of material interests does not completely rule out compromises and good faith acts of solidarity that may involve sacrifices in service to higher principles — as long as such sacrifices are fully reciprocated.